Do you have scraps of faux fur leftover from other projects? Or maybe you have other fur items you’d like to repurpose into something else? Try making just 2 pompoms, and you may become “pompom crazy!” A major symptom: embellishing everything in sight with puffy little faux fur pompoms.

Do you have scraps of faux fur leftover from other projects? Or maybe you have other fur items you’d like to repurpose into something else? Try making just 2 pompoms, and you may become “pompom crazy!” A major symptom: embellishing everything in sight with puffy little faux fur pompoms.

At a glance, tracing circles on fur scraps may appear to be a child’s craft…and it very well could be. On the other hand, high-fashion furriers use pompoms as zipper pulls, whimsical embellishments, to finish the ends of a scarf, and so much more.

Let’s get started!

- Trace the pattern on the fur backing, or simply trace a 4″ round lid, cup, etc. on to the back of the fur piece (Figure 1).

- With a snipping motion—and cutting through the backing only—cut out the circle.

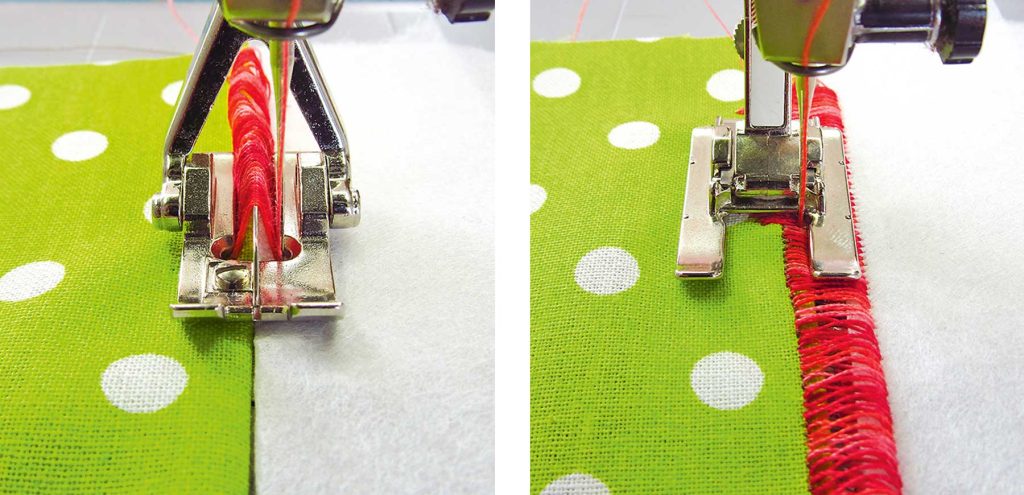

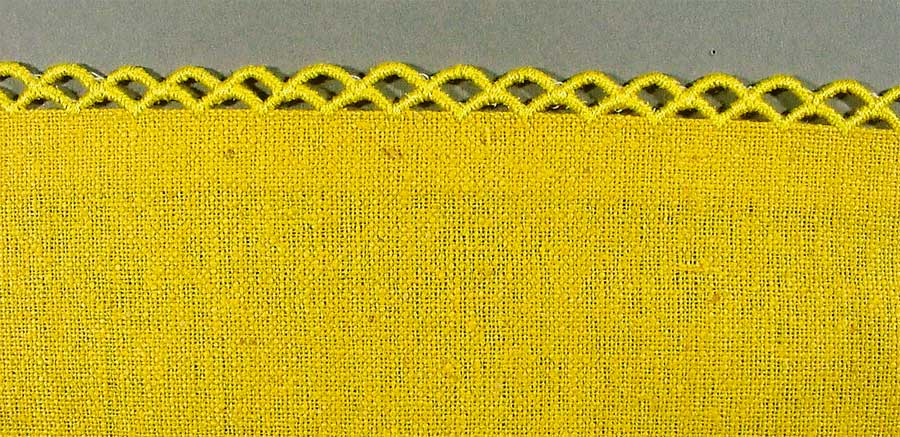

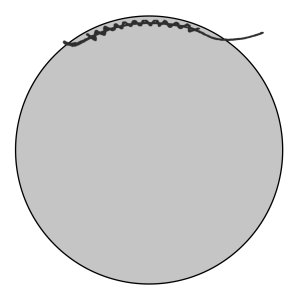

- Set your machine stitch for a long, wide zigzag stitch (4W,4L).

- You’ll need 13 inches of strong cord such as twine, yarn, or a double strand of ordinary sewing thread.

Because fur is so forgiving, thread color matching is unnecessary so use whatever color of thread is currently in your machine.

- Using the zig-zag setting, stitch close to the edge with the backing side up and the cord, twine or doubled sewing thread centered under the zigzag stitching (Figure 2).

- Sew completely around the circle, back-tacking at start and finish.

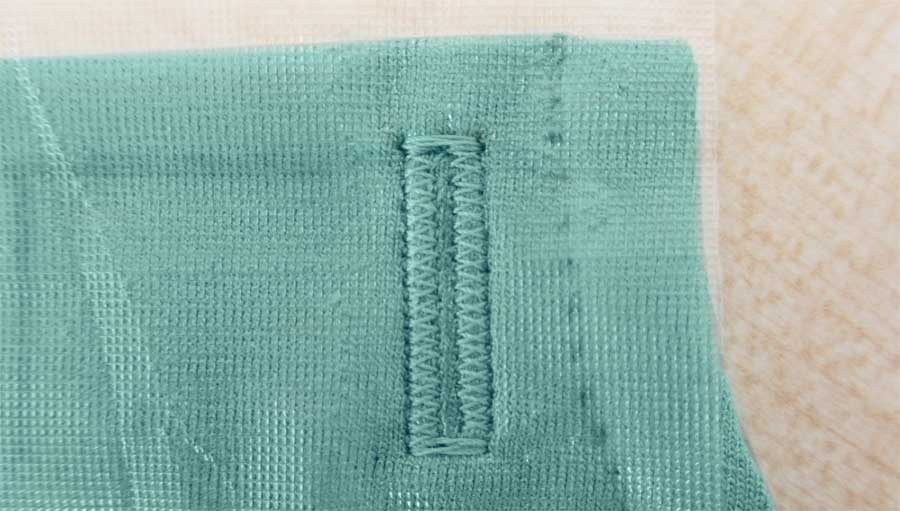

- Grasp cord ends and pull up gathers (Figure 3).

As if by magic, a puffy ball forms. Tie off the cord, leaving ends long enough for securing the pompom to whatever you embellish.

If your pom-pom needs some pouf, stuff lightly with cotton balls.

For a Zipper Pull

For a Zipper Pull

- Tie a pompom to a zipper pull. just as furriers do on S5.000 jacket.

For a Hair Tie

- Secure a pompom to an elastic hair band for a pony tail with panache.

For a Velvet/Fur Tie

- A length of black velvet cord and two pom-poms. one black. one white, equals a hair tie with star quality.

For a Neck Accessory

- For a fabulous holiday look, wear the above velvet! fur tie at the neck of a silk shirt.

For Everything

- Add fur pompom to everything: a knit cap, scarf ends, shoe tops, draw cord ends, shoe ties, or slippers.

- Sprinkle a faux fur jacket or wearer with fur pompoms.

- Use as buttons.

- To change the size of the pompom, just change the size of the circle.

~Based on an article by Donna Salyers, Fabulous Furs