Some things we do with our sewing are meant to be seen, others are purposely meant not to be seen but are still important in the construction process. Understitching belongs in the latter category.

What is understitching?

It’s a line of straight stitching used to help keep facings in their place and tucked under the edge they’re finishing. You may have seen some necklines or armholes without understitching, and what do you see? A facing poking out and not staying in the place it was intended to be. Understitching goes through the facing layer and the seam allowances of the garment it’s attached to; so three layers, plus any applied interfacings. In most instances, understitching is done with a straight stitch. It shows only on the inside of the garment and not the outside, though its absence is often visible with roll-out edges.

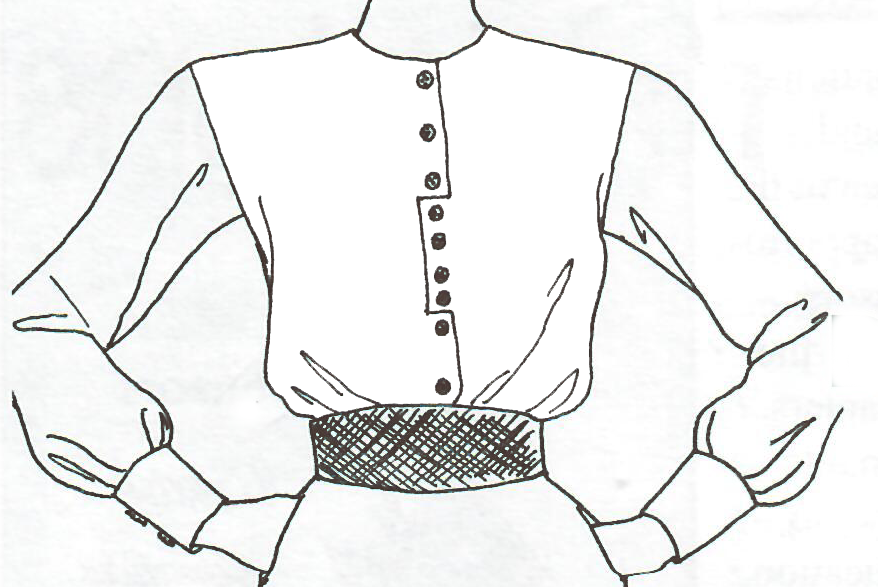

In addition to armhole and neckline facing areas, understitching can be used on opening edges (front or back) and even when a garment is lined to the edge, like a skirt waistline opening. If your facings are a contrast fabric to the outer garment fabric, understitching is especially important to keep them hidden.

If there’s a collar, ruffle or trim band on the garment, understitching is imperative. The more layers you’re trying to control, the more important it is to understitch.

Understitching is not the same as topstitching. Though their functions can be the same—holding edges in place–topstitching is meant to be seen on the outside of the garment, understitching is visible only on the inside.

Understitching know-how

Most understitching is done by machine, though on heavy wools, fleeces, etc. it can be done by hand for better control.

The straight stitch setting is all you need for understitching most garments, with about 10-12 stitches per inch. On thicker fabrics, you may opt for a zigzag or serpentine stitch for better control of the bulky layers. Remember, it doesn’t show, so you can even choose a decorative stitch if you prefer, just for a smile when you don the garment.

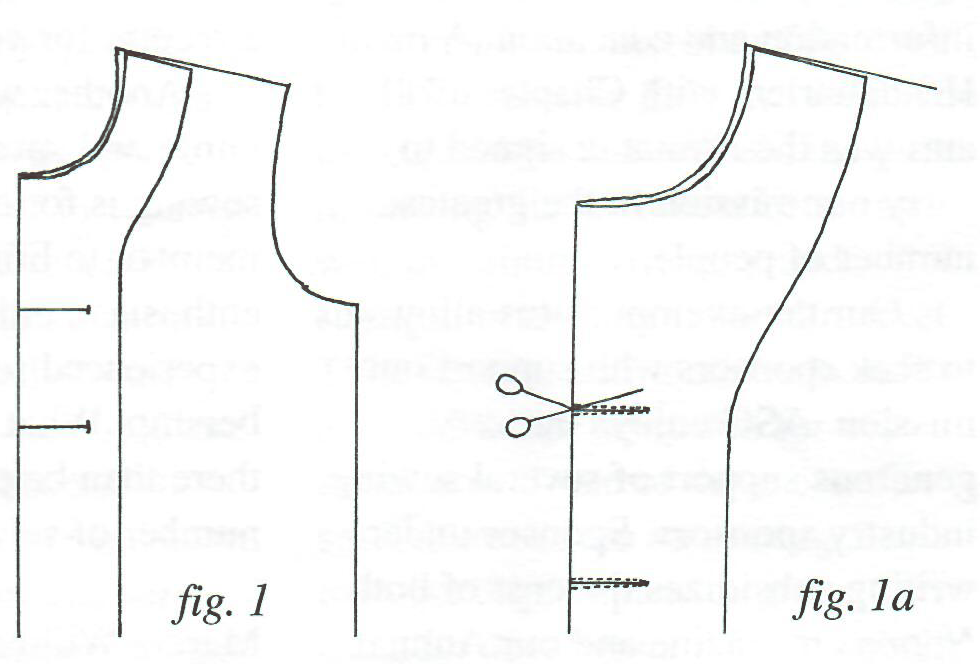

To create understitching, follow the pattern instructions to apply the facing or lining to the opening edge. After completion, trim and grade the seam allowances and clip any curves. When grading, be sure to keep the longest seam allowance to the outside as the garment is worn and shortest toward the body. Stagger clips on the various layers to avoid “dimples” in the seam edge.

Firmly press all the seam allowance layers toward the facing or lining. If the garment has a collar, this could be up to six layers, including the interfacings on the collar and facing.

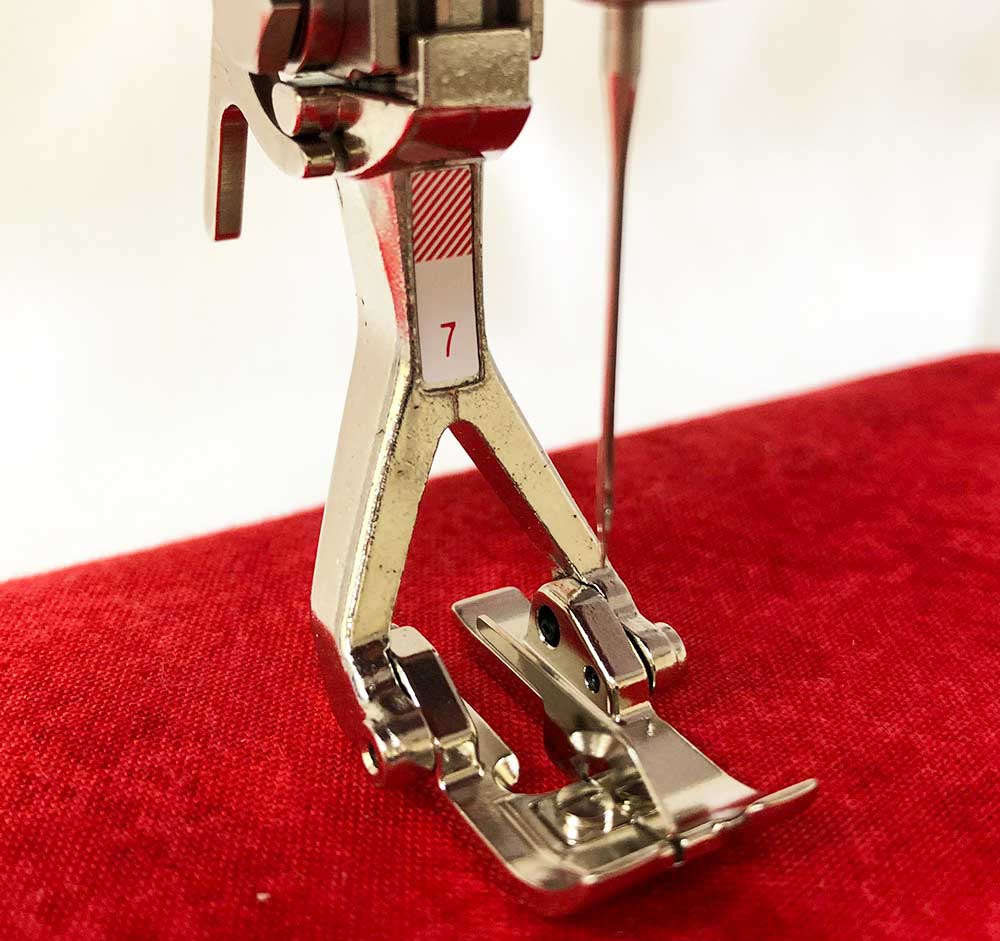

Position the garment under the presser foot with the facing layer right side up and to the right your machine has an adjustable needle position, use it to fine-tune the needle placement near the seam. If your machine has an edgestitching foot, that can be helpful to keep the stitching straight, especially over bulky layers like cross seams. If your garment is lined to the edge, the understitching will be on the lining.

Understitching should catch all the seam allowances under the facing/lining, so keep your fingers underneath the stitching area to be sure layers don’t shift. Graded and clipped seam allowances sometimes decide to turn the opposite direction from how they were originally pressed, so be mindful of that and feel underneath as you sew.

On circular facings, like armholes and neckline openings, understitch all the way around. If your garment has a front or back opening, stitch as far as you can as you approach the corner. Then backstitch to anchor the stitch end.

Finishing touches

Once the understitching is complete, turn the facing again to the wrong side and roll the garment edge ever so slightly to the wrong side next to the facing seam. Tack the finished facing edge to the adjacent garment seam allowancesat the shoulder, side seam, etc. to keep it in place. {photo 4: Finished neckline with understitching}

~Linda Griepentrog is the owner of G Wiz Creative Services and she does writing, editing and designing for companies in the sewing, crafting and quilting industries. In addition, she escorts fabric shopping tours to Hong Kong. She lives at the Oregon Coast with her husband Keith, and three dogs, Yohnuh, Abby, and Lizzie. Contact her at gwizdesigns@aol.com.